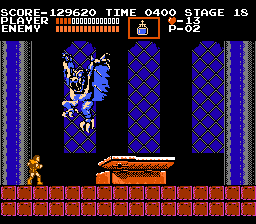

Odallus is the creation of JoyMasher, a Brazilian studio headed by Danilo Dias and Thais Weiller. It's their second game, following 2012's Oniken, with both games being united by a relatively strict adherence to the limitations of the original NES (the studio's next game, Blazing Chrome, moved beyond the NES to more of a Sega Mega Drive feel). Although the 8-bit aesthetic has been very popular among indie developers over the last decade, most such games settle on something that looks NES from a distance but on closer inspection has effects that are beyond what an NES could really do, such as mixed resolutions, going beyond the 4-color limitation, and rotation and scaling effects that were a big selling point of the Super NES. Oniken was very dedicated to being a game that wouldn't look out of place among real NES games. Odallus is much the same, although they've colored slightly outside the lines in certain ways, such as dedicating the screen space beyond the 4:3 gameplay window to character information.

In Odallus, the player controls the somewhat unfortunately named Haggis, who returns home from a hunt to find his village burning and his only son missing. The only thing to do is to head out for revenge and to rescue his boy from the demons that took him. The dark and downbeat story is mostly conveyed through short dialogue segments when facing level bosses. JoyMasher's games so far have all featured a style that is very reminiscent of 1980s and early 90s anime, with a lot of influence from western action and horror movies. Instead of the cute, nonthreatening protagonists popular in modern anime and games, JoyMasher's stern-faced, muscular characters look like they walked out of something like Fist of the North Star, and Odallus in particular feels like a combination of Highlander and Berserk. In terms of how it compares to other games, there's a strong Castlevania and Demon's Crest influence but the dark blue-green colors and grungier feel recall the NES games published by Natsume. Natsume is mostly known today as the company that publishes Harvest Moon, but among their earlier output were games like Shadow of the Ninja, Shatterhand, and Power Blade II - games that come across like moodier takes on the sort of platforming action Konami and Capcom thrived on at the time.

Although Odallus is often described as a Metroidvania, it doesn't have the completely open world of that particular type of game. Instead, the game is broken into distinct levels with multiple exits and the player is encouraged to explore as much as possible, move to the next level, and after obtaining particular items they can then return to previous levels and unlock previously impassible exits to follow a different track for a while. It's more like the structure of Demon's Crest or Demon's Souls. Also like Castlevania, the use of limited secondary weapons is required, although Haggis has the ability to grab ledges and pull himself up, an ability that would have come in handy in many old platforming games.

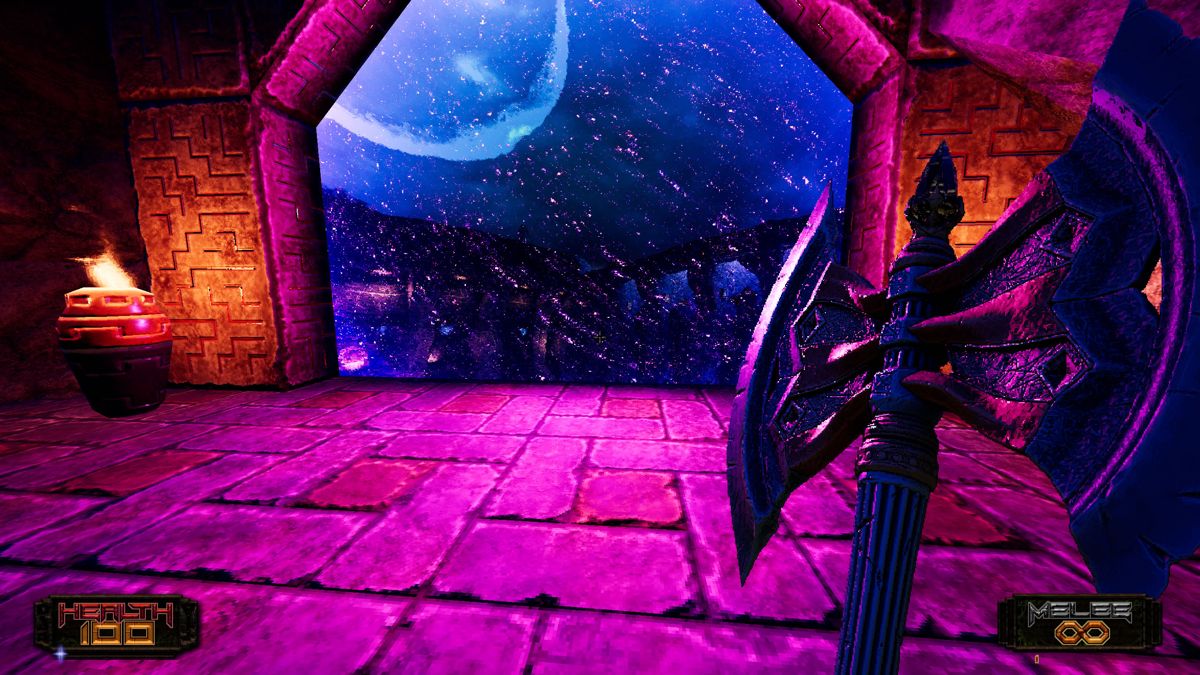

It's a very well-crafted game. Hard enough to put up a solid challenge without leaving the player too frustrated. JoyMasher has been a consistently good studio that works in a style that isn't being covered by many other modern game developers. While many other small developers have been trying to work in a childlike, super-deformed style that has become somewhat standardized, these guys produce games that not only look and sound like late 80s work but also replicate the same kind of easygoing coolness.