Torvak the Warrior is a relatively early game from Core Design, which of course would go on to fame for creating the Tomb Raider series. Torvak is yet another poor barbarian warrior who comes home from the war to find the whole place burned down and all villagers slain by the forces of a necromancer. With no rest for the weary, Torvak picks up his axe and heads off to make the sumbitches pay.

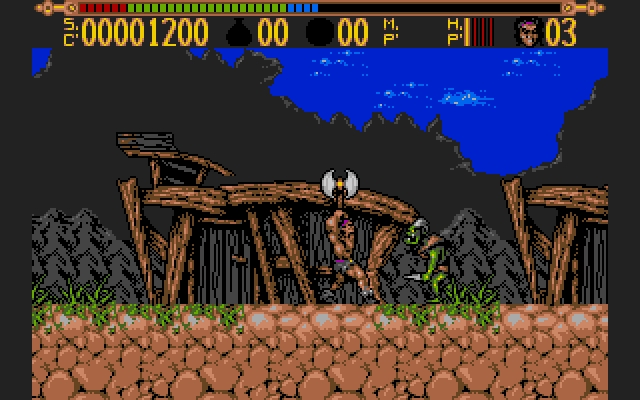

This takes the form of a side-scrolling hack-and-slash game in which Torvak has to generally go from left to right over five levels, but those levels can get a bit mazelike and feature long vertical shafts and hidden secrets that offer extra points and power-up items. Torvak will face human berserkers, green-skinned orcs, rat-men, oozing swamp creatures, and rock-men, among several others.

Torvak begins with his axe but he can pick up a broadsword, a warhammer (leave this one alone, it's terrible), or a ball-and-chain. He can find shields for protection, and he can find potions that allow him to unleash a limited number of magical attacks, handy for facing level bosses.

The game superficially resembles stuff like Rastan, but it's a slow, plodding experience. Torvak, with his top-heavy upper body and relatively stumpy legs, moseys along his way, stops moving while attacking, and since bigger enemies often take multiple hits to kill, he frequently has to take a shot, then leap backwards to create enough space for a second attack. Although he has an explosive jumping ability, he's definitely more akin to Arnold's lumbering portrayal of Conan than Robert E. Howard's quick, pantherish original.

Torvak the Warrior seems to have been initially designed for the Atari ST, then ported to the Amiga, a phrase that probably triggers old Amiga fans' PTSD. The Amiga version got a modest upgrade to Matt Furniss's soundtrack, but nothing else. The relatively limited colors and lack of parallax scrolling betray the game's ST origins, and even the improved soundtrack comes at the cost of forcing the player to choose between music or sound effects, but not both simultaneously, a common issue with Commodore machines because of their limited audio channels.

To its credit, though, the game plays fairly, controls well, and it looks okay even if it's not a technical marvel. Core had some good artists (Lee Pullen and Terry Lloyd in this case), so their games often had a clean, attractive look and distinctive characters. The levels have the standard swamp/mountains/jungle themes, but there are evocative background details like giant skulls and rotting carcasses of huge creatures littering the ground.

Torvak the Barbarian is better than many games, but there are also many games better than it.

Supplemental reading: Legend, by David Gemmell