It seems like there are a couple of particularly strong cinematic influences that keep coming up in sword-and-sorcery games. Conan the Barbarian is the obvious one, and the other is Ray Harryhausen's fantasy movies, mainly his Sinbad movies and Jason and the Argonauts (those reanimated skeletons keep turning up...). Jordan Mechner's Prince of Persia in many ways feels like a Sinbad movie adapted to video game form.

Mechner broke onto the scene in 1984 with Karateka for the Apple II. Karateka, about a Japanese martial artist battling through a forbidding castle to rescue his princess, stood out for its high quality animation and innovative cinematic touches, such as cutting back and forth between the hero and his next enemy as they advanced toward each other and between-level cutscenes that showed the villain scheming. Mechner, never a very prolific game creator, returned a few years later with Prince of Persia, which looks and plays like a refinement of the concepts he was working with in Karateka. The rotoscoped animation is even smoother, the combat is more engaging, and the game is just bigger and more ambitiously designed with its maze-like levels compared to Karateka's strictly horizontal castle layout.

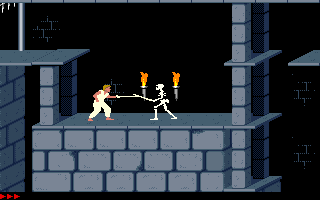

Prince of Persia begins with the sultan's daughter being approached by the grand vizier, Jaffar (it's always Jaffar, why the fixation on Jaffar?), who gives her an ultimatum to concede to marry him within one hour or die. "All the princess's hopes now rest on the brave youth she loves. Little does she know that he is already a prisoner in Jaffar's dungeons...." The player then takes control of the hero, who has just been locked within a...weirdly spacious, multi-tiered cell. Fortunately, a part of the floor collapses under his feet, revealing a tunnel into which he escapes. From here, the player can find a sword that he uses to out-fence guards barring his path and make his way through 12 levels, from the dungeon to the upper reaches of the palace. Along the way, he has to overcome many more guards of increasingly deadly swordsmanship, reanimated skeletons, boobytraps such as spikes that rise up from the floors, and some situations that involve magic, most notably a mirror that creates an evil doppelganger of the hero, before confronting Jaffar in a climactic swordfight.

True to Jaffar's word, the player has one hour of real time to get all the way through the game, although the game does allow a save to be made after level 2 is passed. A good strategy to conserve time is to save at the start of a level, explore until the most efficient route to the exit is found, and then reload and make a serious run to the exit. Most of the non-combat gameplay involves running across platforms, triggering doors to open with pressure plates in the floors (a nod to the death traps in the Indiana Jones movies), and then making difficult jumps across wide gaps before the gates can close. Secrets can be found by probing the ceilings for loose plates. Potions are scattered about that can refresh health or poison the player, and there are some with unique effects, such as one that allows the prince to fall like a feather. Combat is simple - the player can lash out with his sword, or perform a parry, and timing and positioning determine if a hit is scored. The combat was designed so that when the hero and an enemy are going full speed, it would resemble the fencing in swashbuckling films like The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Prince of Persia effectively established a new subgenre of games that people took to calling "cinematic platformers" because of the way they often use rotoscoped animation and relatively realistic characters, emphasize cinematic storytelling, and stress a more measured, careful style of play compared to standard platforming games like Super Mario Bros. Games that followed Prince of Persia include the French-made Flashback and Another World (aka Out of This World), Blackthorne, Nosferatu, and The Way, among others. It could be argued that the original Tomb Raider games adapted the genre to work in 3D, as they also emphasize platforming challenges with a frail, somewhat realistic character. The way Lara Croft has to carefully get in position to make leaps is very much akin to how cinematic platformers work.

The game has excellent art direction. The smoothness of the animation - the rotoscoping was based on films of Mechner's brother - was really striking at the time, and the graphics effectively bring across the Middle Eastern atmosphere without requiring a lot of clutter on the screen. The game looks only as detailed as it needs to be. Once you know the controls and move around a couple of screens, you just get how you need to play the rest of the game. Some welcome touches include that the enemies are just as vulnerable as you are - if you harry them backward off a ledge or into a trap, they'll die as surely as you would - and spike traps can be passed if you walk carefully through them instead of the instant-kill-on-touch quality seen in most games. The music, composed by Mechner's father, is sparse but also memorable. There's a rare sense of elegance and restraint in every aspect of the game's design that also extends to how the game handles the sorcerous elements. The game might involve sword-swinging skeletons and mystical doppelgangers, but it still feels like a relatively naturalistic world compared to the crazed delirium the afflicts most games in historical settings (and movies that are inspired by such games). You're just a man trying to rescue his lady from a sorcerer and his minions in a castle. There's no need for the whole planet to be in jeopardy from armies of flame-puking demons rampaging everywhere (not that that can't be fun in the right hands...).

Supplemental reading: Desert of Souls, by Howard Andrew Jones

No comments:

Post a Comment