It's hard not to figure that an action-packed battle to slay a vampire or some other monster isn't a classic S&S premise. For instance, Conan versus Akivasha in The Hour of the Dragon. Karl Edward Wagner's Kane fought werewolves in Reflections on the Winter of My Soul. Much like how Konami's Contra is basically "Rambo and Commando vs. Aliens," Castlevania can be boiled down to being about a Conan-like hero using a whip to fight his way through the entire Universal Horror pantheon, albeit with some tweaks for legal purposes and some other monsters from western culture thrown in to pad out the rogue's gallery.

The original Japanese title is Akumajo Dracula, for which the closest translation appears to be Demon Castle Dracula. The Japanese title was considered a bit too satanic and therefore religious to get past Nintendo's strict "no religion" censorship policy, so it was retitled Castlevania in the West. The hero is named Simon Belmont, who travels to Dracula's castle to eliminate him, armed with a magical whip called the Vampire Killer. The oddness of a vampire hunter using a whip is often remarked on but the reason is simply that the creators of the game were big Indiana Jones fans and thought the whip would be cool.

Director Hitoshi Akamatsu grew up a fan of the Universal horror movies and he wanted to create a game that was very cinematic. The title screen scrolls in sprocket holes at the edges of the screen and there's a moody cinematic showing Simon approaching the gates. Upon finishing the game, the player is rewarded with fake end credits that list names inspired by classic horror icons Terence Fisher, Christopher Lee, Boris Karloff, and...Jean-Paul Belmondo?

By the time Castlevania came along, video games had evolved from single-screen concepts that demanded quick reflexes and pattern recognition skills for success toward broadly scrolling games that emphasized memorization of level layouts and placement of enemies and traps. Although it's a challenging game, it can be overcome by simply learning where everything is and working out the correct sequence of actions to navigate a section, almost like a puzzle. Simon can't walk and attack simultaneously and the arc of his jump is fixed, so restraint is helpful in determining when to strike and when to move. Success can be made much easier if the player picks up the right alternate weapons depending on which level boss is being faced. The axe works well for the giant vampire bat, while the watch that stops time is deadly to Medusa. The holy water is generally best because it can freeze many enemies while doing constant damage.

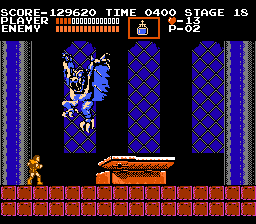

Graphically, the game is especially nice-looking for an NES game. Although the system wasn't much for shadows, especially at that period, the game features moody colors with lots of deep reds and blues and well-proportioned, naturalistic figures. The best part of any Dracula adaptation is the beginning in his crumbling, cobweb-ridden castle and the game wisely is based entirely around that. Simon begins outside the moat, makes his way over the drawbridge into an entrance hall lined with ragged drapes, and eventually will pass through bone-strewn dungeons and the water-logged foundations crawling with fish-people, ascend a clocktower, and then finally penetrate Dracula's tower. It's an internally consistent pattern that worked so well that most of the game's sequels adhere relatively faithfully to it. There are various embellishments but the general map doesn't change much. Lastly, all the Castlevania games are renowned for their soundtracks and this one got the series off to a great start.

Akamatsu apparently wanted to set the game up for sequels, much like horror films often do. An idea that doesn't come across clearly in the game is that Dracula doesn't become a demon or reveal a second form after his health bar is depleted, but his head flying off and his body exploding were supposed to be his actual body scattering across the earth, leaving open the possibility of his resurrection (which indeed became the basis of the second game as Simon returned to track down Dracula's body parts). The demon the player fights afterward is supposed to be an embodiment of sin or "an incarnation of the curse of man," insinuating that Dracula's persistence is tied to the darker side of human nature. Akamatsu also clarified that the clock tower, a fixture of the series, is supposed to represent Dracula's heart.

It's a classic game that holds up well and kicked off a series that remained relatively consistent in high quality despite some significant evolutions in gameplay, even if the expansions of the backstory became confusing and somewhat watered down the gut-level appeal of simply battling Dracula, the Mummy, and Frankenstein's Monster.

No comments:

Post a Comment